Rachel Lichtenstein – The Stories We Tell

15 Jul 2020 / The Stories We Tell

Disappearances and Encounters

As the daughter and granddaughter of antique dealers, I grew up handling wonderful old things. They came briefly into the house before being sold on at Portebello market, and I was only allowed to touch the objects which had been acquired in lots from auction houses. Many of these items had been stored in attics for decades in old tea chests. They rarely had much monitory value, but to me they were magical.

I remember examining a broken Victorian brass microscope with glass slides filled with pressed butterflies wings; a memorial death ring with a lock of braided human hair; tinted postcards from all over the world written in the same sloping hand; an inlaid wooden musical box with ivory keys. My favourite childhood game was to hold these belongings in my hands with my eyes closed, and to try to imagine who had owned them and where they had come from.

I have always been a storyteller fascinated by the traces of the past that get left behind, whether they are salvaged mementoes from an abandoned building, the fading memories of a rapidly disappearing landscape, or the hidden narrative within a single photograph. I think this particular curiosity developed in childhood. My grandfather, Gedaliah Lichtenstein, was an antique dealer and a watchmaker who shared a stall with my father at the London market. After he died, I gathered his watchmaking tools and other ephemera and family memorabilia from his shed, objects which would later form the basis for my degree show in Fine Art sculpture at Sheffield University.

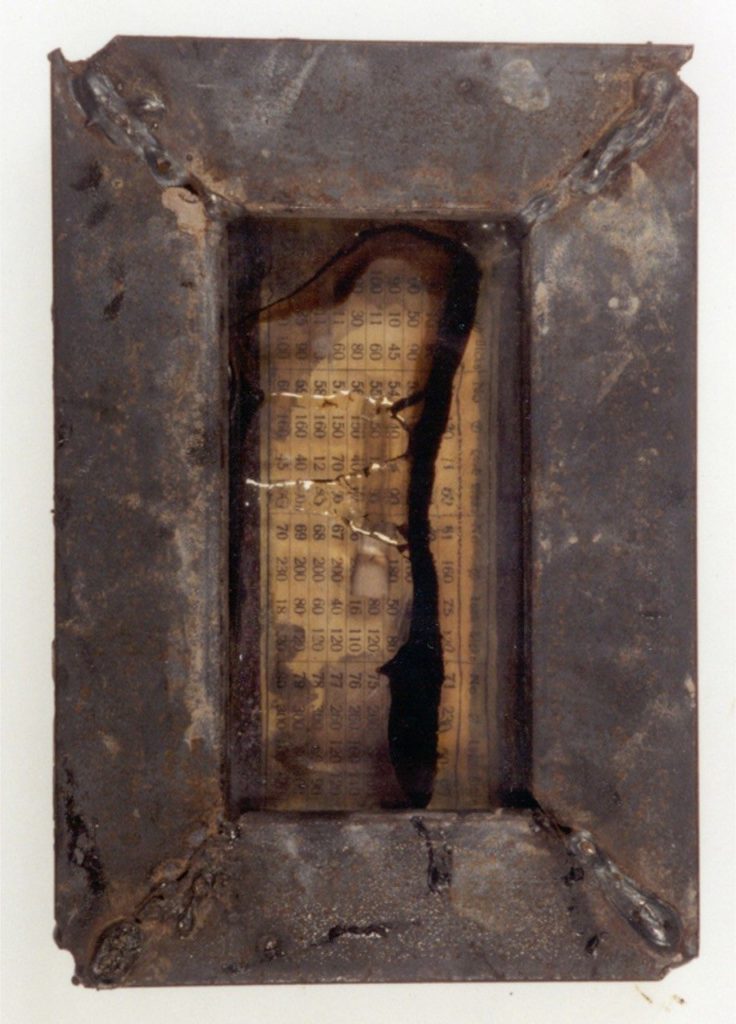

‘Ner Htamid’ – ‘Eternal Lights’ – consisted of twelve small sculptures: welded steel frames filled with objects sealed in resin; the face of a watch; a pickle fork on a bed of lace; an unnamed portrait of a mother with two infants taken outside a wooden home somewhere in the Polish countryside. A desire to find out more about my grandfather’s past led me to undertake many journeys. I went repeatedly to Poland, where he had been born, to New York, where family members had lived, and to the Princelet Street Synagogue in East London, where he had married my grandmother Malka Kirsch in the 1930s.

As soon as I entered the Princelet Street Synagogue, I knew I had to spend time there. The place looked exactly like the abandoned synagogues I had seen the summer before in Poland whilst exploring my Jewish heritage. I took up a position as the unpaid artist-in-residence and started to explore the local area on foot, taking photographs and recording stories of former Jewish residents of that place, including members of my own family. During this time, I showed the sculptures I had made in college in the window of C.h.N.Katz’s String Shop on Brick Lane, one of the last Hasidic-owned businesses in the area. The writer Iain Sinclair saw this installation during one of his ‘drifts’ through Whitechapel, and later wrote about the artwork in Lights Out for the Territory (1997).

I started to collaborate with Iain Sinclair from this time onward, on various projects, including an experimental film in the attic of the Princelet Street synagogue about David Rodinsky, an orthodox Jewish scholar who had lived in those rooms and mysteriously disappeared in the 1960s, leaving everything in place. When Iain Sinclair launched Lights Out in a former abattoir in Smithfield meat-market, he invited me to relay the story of my research in the synagogue. In the subterranean cellar of the building, I projected film footage of Rodinsky’s abandoned attic, played audio clips, showed my photographs of his belongings and described related encounters with people and places connected to the research. Sinclair’s literary agent at the time witnessed this performance, then suggested I write a book on the subject. Rodinsky’s Room, co-authored with Iain Sinclair, was published over twenty years ago now.

When Rodinsky’s abandoned room was unlocked for the first time in 1980, it looked as if it had been frozen in time, with everything more or less in its original state, even down to porridge on the stove and the imprint of a head on a pillow. Tucked inside books scattered around the room were notes written in ancient scripts. Dictionaries of dead languages lay stacked in towers upon the floor. A whole notebook was filled with Irish drinking songs, and beneath a wardrobe lay a crumpled, cabalistic diagram. Everything in the room sat waiting beneath a layer of dust.

Rodinsky’s Room tracks my journey to uncover his story – in a series of examinations of his vast collection of belongings – as I make multiple journeys to Poland, New York and back to London again. The text weaves together my quest for Rodinsky and my own Jewish heritage – with Iain Sinclair’s meditations on this journey and his own reflections on Whitechapel. Rodinsky’s Room became a testament to a world that has all but vanished, and a homage to a unique culture and way of life which has now disappeared from that area forever.

Since the publication of Rodinsky’s Room, I have written a further three creative non-fiction books alongside the ongoing production of my artwork. All my multi-disciplinary work, as both a writer and an artist, explores the complex layering of historical experience and memory in direct relation to places past and present. I’m fascinated by themes of identity and loss; by fragmented histories and the haunting of the disappeared. The stories I tell are collaborative. They include multiple voices and encounters, with both landscapes and people alive and gone, individuals who are in different ways connected to the places I investigate.

Once I have identified the subject I want to examine – often a physical location – I spend a lot of time immersing myself in that place, exploring its history, geography, legends and tales from as many different perspectives as possible. I need to have a really sustained commitment to a subject, as I work very slowly, and the research for the books I write often takes years to complete. I normally start by walking repeatedly across the same territory, taking photographs and making audio and visual recordings. I often conduct these wanderings alone, but sometimes I ask different people to join me who can help me either visualize the past or understand these landscapes from a different perspective. These experts range from archivists, geologists, archaeologists and historians to poets, artists and photographers, as well as individuals who have lived and worked in these areas, and who have come to know these places intimately over time.

To attempt to uncover the deep-historical past of a place, I also spend a great deal of time in archives and libraries researching that place, a process which I find immensely pleasurable. The unfurling of the layers of stories is an endlessly exciting activity; there is always the possibility of peeling back the veil of time, to glimpse a moment of the past, to ‘see’ a landscape from a bygone era. The greatest joy of my working life, however, is the conducting of oral history interviews. It is a privilege to hear, first-hand, and often for the first time, the stories of ordinary people’s lives.

My research has taken me to many places since writing Rodinsky’s Room, from the diamond district of London’s Hatton Garden, to the naval sea-forts in the middle of the Thames Estuary, to the coastal fishing town of Speightstown on the Caribbean island of Barbados. But I return, again and again, to the first landscape of my imagination: the former Jewish East End of London.

During all the years I spent undertaking research and living there, I met many older Jewish residents of that place, and I recorded their stories. They talked with great sadness, and with an acute sense of nostalgia, about the Whitechapel of their youth, the crowded Jewish centre of London. They recalled a place bursting with life; a place of ‘stink’ and ’wonderful smells’; the lively markets. They remembered the Russian Vapour Baths where ‘the devout Hasidim with their sidelocks, long black coats and beards would wait to get into the steam baths before Friday night services’. They described pre-war Whitechapel as one big working Jewish settlement.

When I first moved to the area thirty years ago, there were many tangible remnants of former Jewish occupation in the area: the marks of a mezuzah on a doorpost; a faded name written in Yiddish above a boarded-up shop; a bronze star of David above a gentleman’s outfitters on the high street, a star blackened by the smoke of car exhausts. There were even a few Jewish-owned businesses and institutions still operating – down-at-heel delicatessens, kosher eateries and bakeries, and a smattering of functioning synagogues. Today only a few physical traces remain, such as the façade of the former Jewish Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor, Nos. 17–19 Brune Street. Even the Jewish Memorial showroom in the area has recently closed down. Jewish Whitechapel has become a shadow realm, a theatre of memory invisible to the present-day visitor, and impossible to navigate without an expert guide.

When I first moved to the area thirty years ago, there were many tangible remnants of former Jewish occupation in the area: the marks of a mezuzah on a doorpost; a faded name written in Yiddish above a boarded-up shop; a bronze star of David above a gentleman’s outfitters on the high street, a star blackened by the smoke of car exhausts. There were even a few Jewish-owned businesses and institutions still operating – down-at-heel delicatessens, kosher eateries and bakeries, and a smattering of functioning synagogues. Today only a few physical traces remain, such as the façade of the former Jewish Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor, Nos. 17–19 Brune Street. Even the Jewish Memorial showroom in the area has recently closed down. Jewish Whitechapel has become a shadow realm, a theatre of memory invisible to the present-day visitor, and impossible to navigate without an expert guide.

Recently, I have been working on a new collaborative digital resource with colleagues at the Survey of London and University College London. It brings some of this lost history back to life. The interactive Memory Map of the Jewish East End includes excerpts from my substantial archive of oral history recordings with former and current Jewish residents of East London I have interviewed over the years, many of whom are sadly no longer with us. Hundreds of archival photographs can also be accessed on the map, along with original research. You can visit the map here.

I thought that working on this project might fulfil my desire to document and record the stories of the former Jewish East End, but instead it has made me acutely aware of the vast gap in our knowledge of women’s experience in this place. I am now working on a new book, which may also become an exhibition and a digital project; it explores the stories of women in the Jewish East End.

I start with the story of my grandmother Malka.

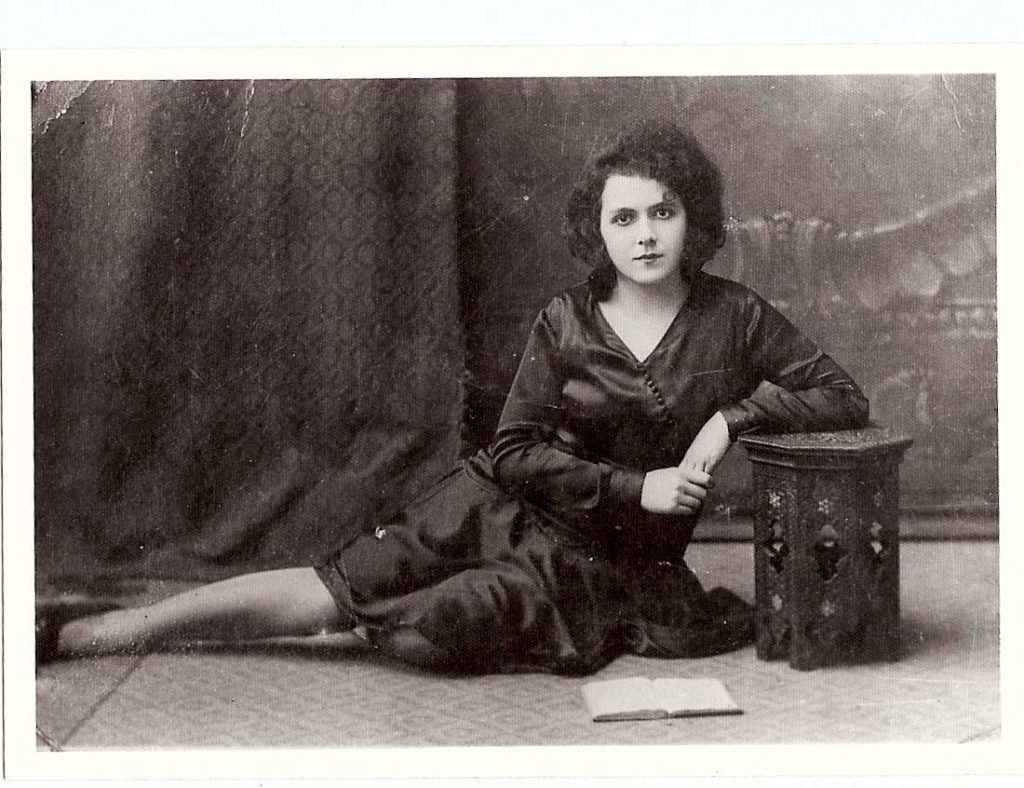

She died when I was just ten years old. I remember her as a very glamorous, somewhat remote, larger-than-life character, with great curly beehive wigs, diamond jewels, fox furs, velvet cloaks and gold teeth. She was a funny, slightly intimidating, but incredibly warm Yiddishe bubbe (Jewish grandmother) who never lost her strong Polish accent.

There were few visible signs of her Eastern European past in her house, apart from one large framed family portrait in the front room. The fate of the people in that picture was never directly discussed when I was growing up but, after asking many questions of relatives in later years, I learned that just seven out of the thirteen survived. The only obvious outward manifestation of the great losses she had suffered was her crushing anxiety. If we were five minutes late she would be pacing outside the house hysterically. She wanted her family close. If she could not get hold of us, she panicked.

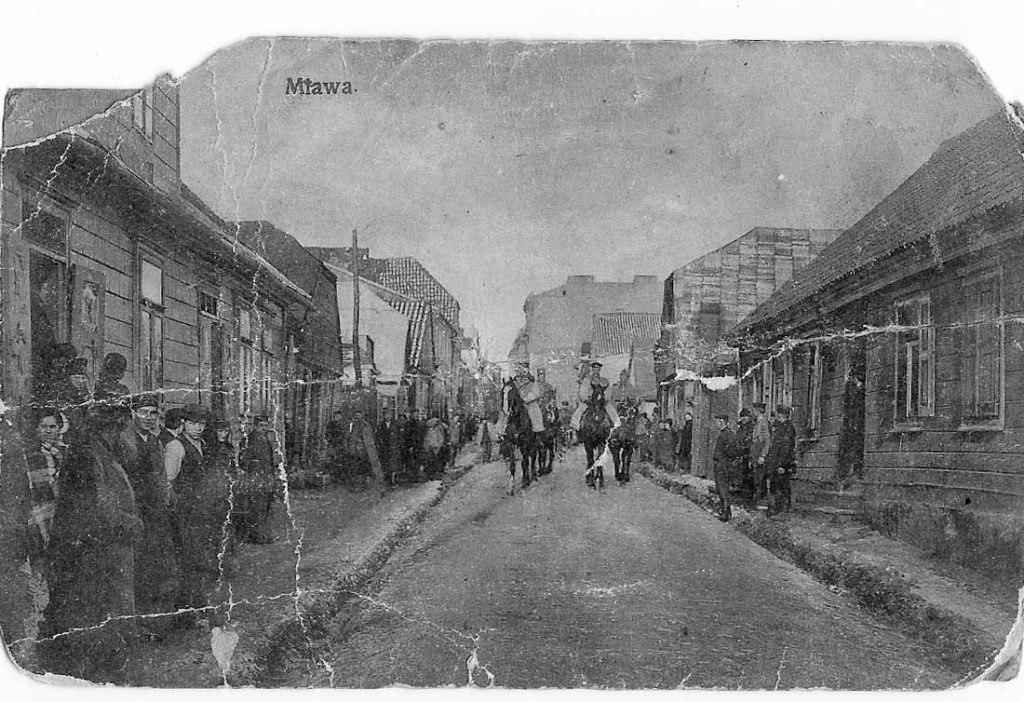

After she died I found a crumpled postcard in her bedside table of the place where she had been born, which was called Mlawa. The image on the front of the postcard looks like a real-life Anatevka, the shtetl, or small market town depicted in the 1971 film Fiddler on the Roof, which was based on Tevye the Dairyman and other tales by Sholem Aleichem. The postcard showed a narrow unpaved muddy road surrounded by low ramshackle wooden buildings. I asked my father if he knew anything more about Mlawa, but he said his mother never spoke about it, before adding, ‘There’s so much that I wished I’d talked to her about, but I never did. As a child you’re not interested, and my mum’s been dead forty years next year.’

Today Mlawa is a large municipality in north-central Poland, but when Malka lived there in the early twentieth century, it was a frontier town in the captured Russian territories known as the Pale of Settlement. Close to the Imperial Prussian borderlands, and witness to heavy fighting between the opposing German and Russian armies, it was a place interrupted by violence and uncertainty. Nearly half the population of the town were Jewish back then. They lived predominately in the poorest district, which had been established originally in 1824 as a Jewish ghetto. For most it was a hard, poverty-stricken life, one which mirrored the lives of hundreds of Jewish communities in shtetls across ‘the Pale’, a life bounded by tradition and the Jewish calendar, with Anti-Semitic attacks a regular occurrence.

At some point after the First World War, Malka made her way to East London to join her elder brother Joe, who had fled to escape conscription in the Russian army. The exact details and dates are unknown. My father thinks she got the boat from Hamburg to London, and most likely walked part of the way, then took the train. ‘It was a well-established route because thousands of Jews left Poland around that time,’ he said.

Malka lived with her brother Joe, his wife Rebecca, who was also a refugee from Mlawa, and their youngest child Sidney in a few rented rooms in a house in Cleveland Way in Whitechapel, a house shared with two other families. The family was incredibly poor. They struggled to pay the rent and put food on the table. There was a close-knit Jewish community living nearby, and Sid remembered his mother going to Hessle Street market to buy a live chicken and have it slaughtered.

They kept a traditional kosher household and celebrated all the festivals together. ‘The whole area was full of Jewish people, we didn’t have non-Jewish friends.’ He remembered Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah as big occasions when the family would fast, then come together for celebratory meals. He talked of visiting the small synagogues all over Whitechapel, moving from one to another, and of going to the cinema and the Yiddish theatre with Malka, who was very attractive and loved to dance and sing. She had a beautiful voice and was in many choirs.

Early photographs of her in London in the 1920s show a glamorous young woman who appeared to be embracing her new cosmopolitan life. She clearly loved dressing up in the latest fashions and having her portrait taken at one of the many photographic studios that had sprung up in Whitechapel for the thousands of Eastern European Jews who were arriving daily in East London at this time, many of them eschewing their restricted religious upbringings.

In 1925, Malka started to learn English at evening classes on the Whitechapel Road. She met her future husband there, my grandfather, Gedaliah Lichtenstein, another Polish émigré, and they married in 1932. Their first marital home was above their watchmaking and clock shop, on the corner of Brick Lane and Princelet Street. The story has come full circle for me, back to the place where I wrote my first book, as I start to uncover the stories of the next.

Dr Rachel Lichtenstein is a writer, curator, artist and Associate Professor of History and English at Manchester Metropolitan University, where she co-directs the Centre for Place Writing. Her publications include Estuary: Out from London to the Sea (Penguin, 2016), longlisted for the Gordon Burns Prize; Diamond Street: The Hidden World of Hatton Garden (Penguin, 2012); On Brick Lane (Penguin, 2008), shortlisted for the Oondatje prize; Keeping Pace: Older Women of the East End (Women’s Library, 2003); A Little Dust Whispered (British Library, 2002); Rodinsky’s Room with Iain Sinclair (Granta, 1999), now considered a cult classic – this book has been translated into five languages. Her artwork has been shown at the Barbican Art Gallery, the British Library, Jerusalem Theatre (Israel), Wood Street Galleries (USA), and Whitechapel Gallery, among other places.